Parental Bonding and Trich: What’s The Connection?

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

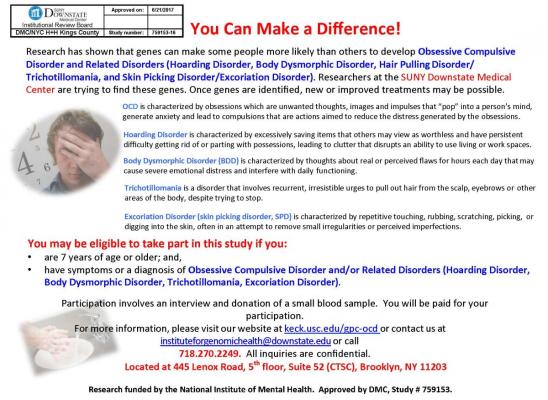

Body focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) often first appear in childhood or early adolescence. It is not clear exactly why some children develop a BFRB while others do not. What we do know is that many mental health disorders can be influenced or shaped by both genetics and by environmental factors, including family dynamics. For children, that usually means interactions with their parents.

Research into child mental health tells us that parenting style can play a key role in a child’s mental health and ability to cope in healthy ways. With all of the research that has been done in this area, it is surprising that there has been little attention paid to parent-child dynamics in BFRBs like trichotillomania (TTM). Family dysfunction has been associated with children who have a BFRB, but family dysfunction is a broad construct, and the relationship is not clear. Does the parent-child relationship influence the development of a BFRB like hair pulling, and if so, how? A newly published study seeks to look at that very question. What the study has found might surprise you.

The Importance of Parental Bonding

Now, to be clear, parent-child dynamics do not cause someone to develop a BFRB or any other mental health issue. There does seem to be some association between parent-child dynamics and a child having a BFRB. Just how that relationship affects the development of a mental health issue isn’t completely understood. The relationship between a parent and child is a dynamic and complex one, not easily defined.

One of the most significant factors that influence parent-child relationships is the degree of parental bonding. Parental bonding is the attachment that forms between parent and child. It is this bond that creates a sense of security, connectedness and being cared for. These bonds develop over time and set the stage for the child’s later adjustment and functioning.

Parental bonding is often measured along the dimensions of:

- perceived parental care (expression of affection),

- parental protection (parental encouragement to explore the environment), and

- the balance of these two variables, before the age of 16.

These dimensions combine in ways that characterize four styles of parenting:

- Optimal parenting (high care/low protection)

- Affectionate constraint (high care/high protection)

- Neglectful parenting (low care/low protection)

- Affectionless control (low care/high protection)

Each of these parental bonding styles can influence the parent-child relationship and the child’s emotional development.

Why look at parental bonding and BFRBs? Problems with parental bonding have long been suspected to play a part in the origins of BFRBs. Personality traits associated with TTM, in particular neuroticism, may have an impact on the person’s perceptions of their relationship with their parents.

BFRBs have also been conceptualized as addictions or compulsions. Addiction is also a common co-occurring disorder with BFRBs. Parental bonding has been shown to play a role in these disorders as well with imbalances in perceived parental affection and control.

Parental Bonding and BFRBs

The researchers sought to build upon what is currently known about parental bonding and how it may influence the development of hair pulling or skin picking. What they found was that participants with BFRBs reported significantly lower levels of parental care than those without a BFRB. Only 27% of participants reported receiving optimal parenting.

Participants with BFRBs reported higher levels of both paternal and maternal “affectionless control”. Affectionless control refers to a parenting style where parents are unresponsive to their child’s needs for care while at the same time, hindering the child’s independence. This creates an anxious attachment that can negatively impact the child’s self-identity. This style of parenting has been associated with higher levels of neuroticism and has been linked to substance abuse disorders which often co-occur with BFRBs.

These findings suggest that while low levels of parental care seem to be associated with the development of BFRBs, it remains unclear as to whether or not poor parenting actually predisposes someone to develop a BFRB. It is likely that BFRBs are the result of multiple risk factors with parenting style being one of many to be considered in the understanding of BFRBs.

Nurturing Healthy Bonds

So what does all of this mean for parents and children living with BFRBs? Having a child with a BFRB such as hair pulling can be challenging. Knowing how to help isn’t always clear. The results of the study suggest that nurturing a strong, healthy bond between parent and child (optimal parenting) seems to support good mental health and coping skills.

Optimal parenting is comprised of three key dimensions: structure, affiliation, and autonomy support. Each of these dimensions contributes to healthy emotional development and parent-child bonds.

- Affiliation is characterized by warmth, caring, and acceptance.

- Structure the presence of clear and consistent expectations, boundaries, and consequences.

- Autonomy Support, the opposite of control, is respect for the child’s feelings, ideas, and aspirations, having empathy, and allowing the child to make age-appropriate choices

Parenting optimally doesn’t have to be complicated or out of reach. Being present and engaged you’re your child can help you to create a healthy bond. Parenting mindfully can help you and your child to understand and cope with what’s happening. You can work together to find solutions that work for you as a family and in ways that are nurturing and healing.

Here are some tips:

Don’t Blame Yourself – You are not the cause of or responsible for your child’s BFRB. We cannot predict who will or will not develop certain disorders.

Talk to Your Child – Make time to talk about what’s on their mind. Talk about what they’re experiencing. Let them know you support them and that it’s ok to not have all the answers. It’s ok to ask how they feel. And, it’s ok to “say the words” like hair pulling, too. Let them know that you are always ready to listen when they are ready to share.

Practice Active Listening – When your child is ready to talk, give them your full attention. It takes a lot for them to share feelings that might be uncomfortable or embarrassing. They may not always have the “right” words to express themselves. Try to listen for meaning rather than just for “the words”. Validate their feelings. Be careful to not minimize or dismiss their feelings or tell them why they are “wrong”. Their feelings are very real for them, even if you don’t understand them. Sometimes, kids just need to know, “I hear you”.

Practice Compassion - Don’t scold or punish them for pulling or picking. The urges are beyond what they can control, and they don’t do it for attention or defiance. Let them know you see how hard they’re trying to cope and heal.

Express Affection - Let them know that you love them no matter what and are there to support them.

Set Healthy Boundaries – It can be tempting to ease boundaries or overlook behaviors. Kids need healthy boundaries and structure to successfully navigate their world.

Find A Therapist – Seek out an experienced therapist who understands BFRBs and uses evidence-based treatments. Choose a therapist that you and your child feel comfortable with and trust.

Considering parent-child relationship dynamics is an important part of the development and choice of therapeutic approaches for BFRBs. This study highlights the need for more exploration of the role parental bonding plays and how it can contribute to the treatment of hair pulling and other BFRBs. Learning more about parental bonding offers hope and holds promise for more effective, personalized treatments for those living with BFRBs. In the meantime, strengthening parent-child relationships is a healthy place to start.

References

1. Bögels, S.M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S. et al. (2014). Mindful Parenting in Mental Health Care: Effects on Parental and Child Psychopathology, Parental Stress, Parenting, Coparenting, and Marital Functioning. Mindfulness 5, 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0209-7

2. Valle, S., Chesivoir, E., & Grant, J. E. (2021). Parental bonding in trichotillomania and skin picking disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-021-09961-4

3. Murphy, Y. E., & Flessner, C. A. (2015). Family functioning in pediatric obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12088

4. Parker, G. (1990). The Parental Bonding Instrument: A decade of research. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology: The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services, 25(6), 281–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00782881

5. Grant JE, Chamberlain SR. (2021). Personality traits and their clinical associations in trichotillomania and skin picking disorder. BMC Psychiatr. 21(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03209-y.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW. (2002). Parental bonding in pathological gambling disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73(3), 239-47. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1016044906341

7. Yoshida T, Taga C, Matsumoto Y, Fukui K. (2005). Paternal overprotection in obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression with obsessive traits. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 59(5):533–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01410.x

8. Joussemet, M., Mageau, G. A., Larose, M., Briand, M., & Vitaro, F. (2018). How to talk so kids will listen & listen so kids will talk: A randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of the how-to parenting program on children’s mental health compared to a wait-list control group. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1227-3

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

Start your journey with TrichStop

Take control of your life and find freedom from hair pulling through professional therapy and evidence-based behavioral techniques.

Start Now