Trichotillomania: All you need to know about hair pulling disorder

Trichotillomania, sometimes called trich or compulsive hair pulling, is a mental health disorder marked by the compulsive urge to pull out one’s hair that results in physical injury and impairment in daily functioning.

Trichotillomania

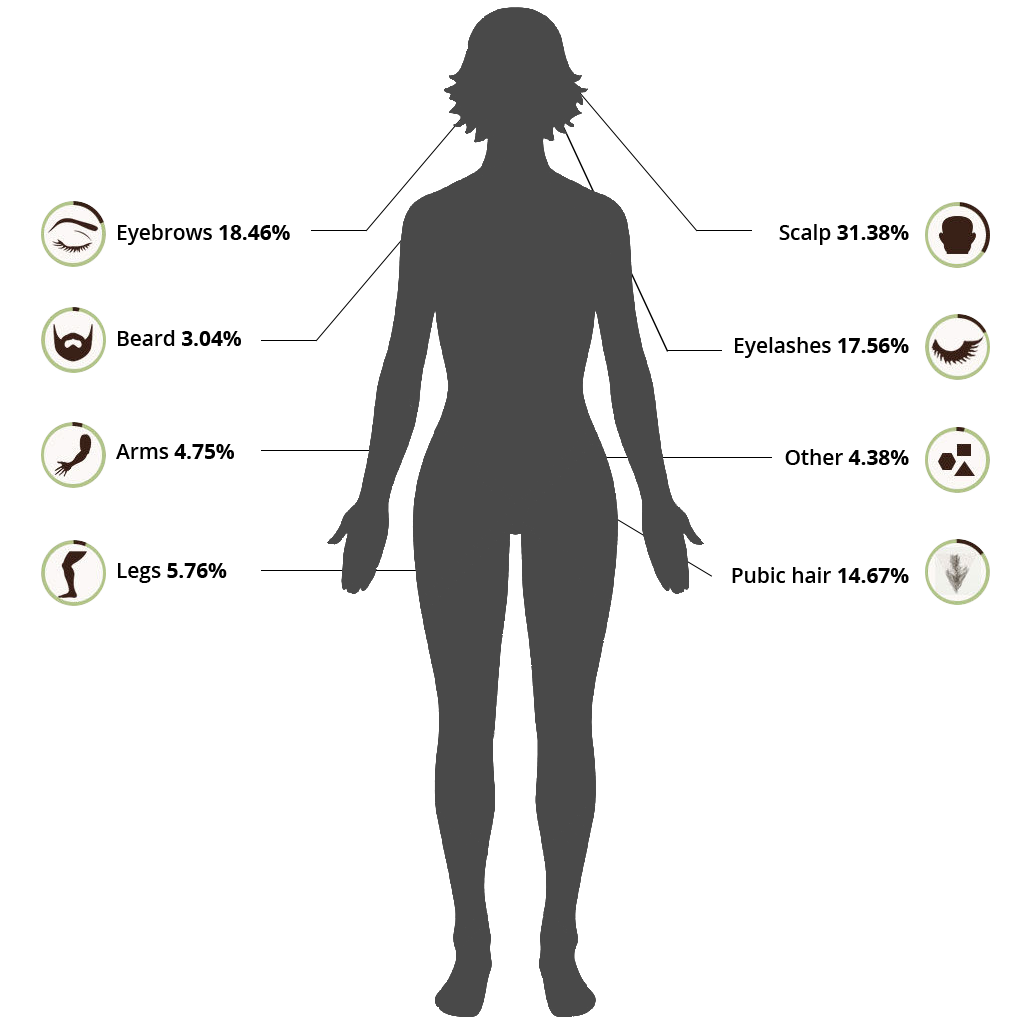

The basic definition of trich is an uncontrollable, recurrent impulse to pull out one’s hair at the root. The target areas for pulling include:

Some people who pull out their hair engage in secondary behaviors such as eating the hair or running it over the skin.

Types of Behaviors

Behaviors associated with trichotillomania manifest themselves on various levels depending on the behavior of the individual.

Automatic

- Pulling occurs outside of awareness

- Usually occurs when bored or “zoning out”

Focused

- Pulling serves a purpose

- May be preceded by physical sensation much like an itch or tingling

- After pulling, feeling of relief or gratification which does not last long

Behaviors after pulling

- Playing with hair after it is pulled out

- Chewing or eating the hair

- Rubbing the pulled out hair across the face and lips

Online Test for Hair Pulling

How Severe is Your Hair Pulling Disorder? Find Out With This Free Online Test

Take the testOnset, Prevalence, and Course

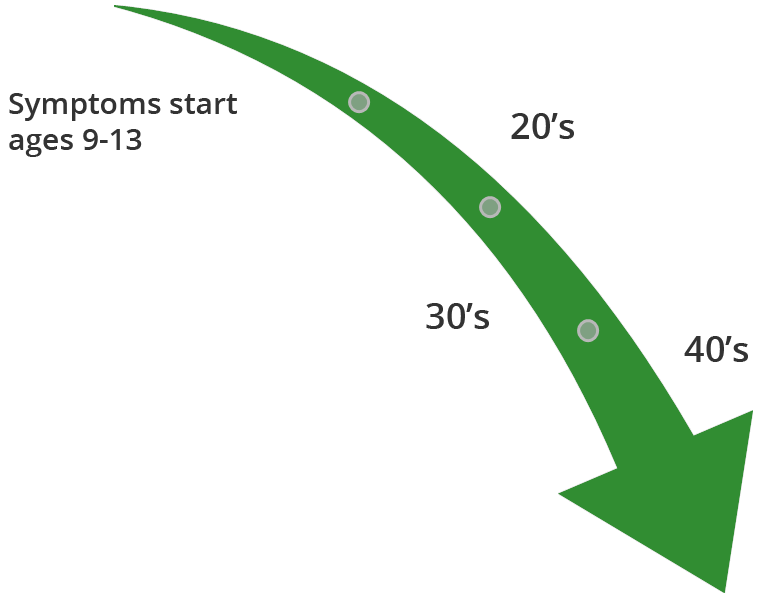

The average age of onset is between the ages of 9 and 13, meaning the urge to pull hair often begins around puberty. Little is known about what starts the symptoms of trichotillomania, but some research indicates depression, stress, or traumatic events serve as initial triggers.

The onset of trichotillomania is also associated with physical injury to some regions of the brain. Research suggests up to 3.6% of elderly patients in residential care for dementia or Alzheimer’s disease develop trichotillomania. With the onset of dementia, the brain begins to change physically, with many areas experiencing atrophy. Repetitive movements increase as the brain changes during dementia. The repetitive movements may include hand flapping, head rocking, leg movements, or body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) such as trich and compulsive skin picking.

Prevalence data suggests that 0.5% to 2.0% of the population struggles with trichotillomania, with adult females experiencing it four times more than adult males. The numbers may not be accurate due to the strong negative stigma attached to the disorder. Many people who struggle with trich choose not to report it. However, prevalence numbers may increase because of the medical community’s increased knowledge and reduction of the stigma surrounding the disorder. The numbers change not because more people have the disorder, but because people are no longer afraid to seek help.

Trich behaviors tend to decrease in severity over the lifespan. The early years are difficult because when it starts during puberty, most people do not understand what is happening to them or why. At this age, the pressures of internal and external stigma also wreak havoc on overall mental health. By the time someone reaches their 20’s, 30’s and 40’s, they have likely sought treatment. Combined with a healthier sense of self that can accompany aging and changing hormones, many people come to terms with and learn to manage the hair pulling behaviors.

Symptoms Severity Decreases Over the Lifespan

Correlates and Causes

The cause of trichotillomania has yet to be determined by the medical field, but there are some theories based in neuroscience. A cause is a physical or environmental determinant of a disorder, something that is directly connected with the disorder.

Correlates, on the other hand, are conditions which occur more often in people with trichotillomania but are not attributed as a cause to the disorder. For example, smoking is correlated with poor health, however, not everyone who has poor health smokes, nor does everyone who smokes have poor health.

Correlates

Research shows that trich is more common in people who have first-degree relatives with OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder) or a BFRB (body focused repetitive behavior), but not all people who have first-degree relatives with OCD or a BFRB have trich. Heredity is not a cause of trich, but suggests there is a statistical association of trich showing up more often in families with obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders.

Another correlate suggests the disorder may be linked to a gene mutation. Scientific studies on laboratory mice with a mutation of the HOXB8 gene, a gene also found in humans, recorded several abnormal behaviors that included hair pulling. The research is limited to mice, however, so there is no way to conclude whether the gene mutation is present in people with trich.

Studies of progesterone levels in women show a positive correlation between trich behaviors and the high progesterone levels of the luteal phase and early stages of pregnancy. Women who have trich, for example, reported that the severity of their pulling behaviors increases during times of high progesterone levels. However, this does not mean that all people with trich will experience more severe pulling behaviors with high progesterone levels.

Some people with trich also report hair pulling behaviors get more severe when feelings of stress, anxiety, or depression are high. The theory is that some people pull hair in a focused way to manage strong emotions. Therefore, pulling behaviors increase to deal with the strong feelings associated with increased stress, anxiety and depression. While this may be true for some people, it is not true for everyone with trich.

Potential Causes from Neuroscience

Differences in brain structure

A recent brain imaging study found “significantly increased cortical thickness in a right frontal cluster.” This region of the brain suppresses inappropriate motor responses. In other words, the part of the brain that tells the body to stop a function is different in people with trichotillomania. The study did not explain how or why the thickness contributes to trichotillomania. It hints at the possibility that the cause of a compulsive movement, such as moving the hands to the hair on the head and pulling it out, can be attributed to a malfunction of the brain mechanism which should say “stop, don’t do that”. According to this theory, the problem is with the brain’s ability to stop a behavior once it starts.

Studies using brain imaging show people with trich have structural brain abnormalities in the lenticulate and the volume of the left putamen. The lenticulate is part of the caudate nucleus of the brain which plays a role in the way the brain learns and regulates the control of impulses between the thalamus and orbitofrontal cortex. Malfunctions in this part of the brain would limit a person’s ability to interrupt worries, obsessions, and compulsions. The left putamen is a part of the brain involved in movement and learning. Studies of Parkinson’s disease and stroke patients show that when the putamen is damaged, the patient will experience unpredictable, repetitive movements. Therefore, malfunctions in the part of the brain that controls compulsions combined with malfunctions in the part of the brain that moderates repetitive movements may explain the chronic nature of trich.

Research of people who develop trich with dementia suggests brain atrophy as a cause. The brain imagery showed the cerebral atrophy in the parietal lobes which coincided with the patient’s restlessness, agitated behaviors, and repetitive, compulsive acts that included hair pulling.

Brain Metabolism

There is evidence suggesting that people with trich have high metabolic glucose rates in several parts of the brain. While this process is a mystery, metabolic disturbances in the brain are associated with other mental health disorders, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. The brain needs the energy to operate; therefore, if the brain’s energy is disrupted in any way, it is safe to assume that brain functions would also be disrupted.

Reward Processing

The rewards processing theory suggests that those who pull hair experience a reward from it thereby creating an altered reward feedback loop associated with the behavior.

Response Inhibition Dysfunction

New research using brain imaging has provided evidence that trichotillomania results from impairment in response inhibition. Primarily, a person experiences an urge to pull their hair, but they cannot resist the urge or stop the behavior even when the response is inappropriate. Some research shows that the part of the brain that tells the body to stop a movement is impaired in people with trich.

Diagnosis

Trichotillomania is a disorder usually hid even from family and friends. So imagine the horror of inviting someone who does not know you into your most intimate and vulnerable secret world. Many people with trich go to a physician or mental health provider to get help with issues that arise secondarily to trich and do not report the real reason for the secondary conditions. As a result, trich is a condition often left undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. A thorough assessment by a trained professional can help distinguish it from other disorders.

Critical diagnostic elements

- A considerable amount of time spent pulling

- Episodes of hair pulling behaviors vary and can be cyclical, but the key indicator is the significant investment of time, sometimes hours per day which interferes with daily life.

- Often, pulling results in changes in a person’s appearance that would cause others to question the changes. Therefore, people spend hours hiding the physical damage caused by pulling.

- Hair pulling results in hair loss and physical damage

- Pulling hair at the roots can cause permanent damage to the skin and hair follicles. In many cases, hair will not grow back resulting in bald spots. If it does grow back, it can grow in patterns that are noticeably different from hair that was not pulled

- When hair is pulled out, the skin can rupture and bleed increasing the risk of infection and inflammation.

- Pulled eyelashes can result in blepharitis, a painful inflammation of the eyelids that itches, burns, and swells.

- Swallowed hair can cause digestive disorders.

- Failed attempts to stop or decrease behaviors

- Many people recognize that compulsive hair pulling is not a desirable behavior and they try to stop.

- Causes significant distress

- Compulsive hair pulling causes stress, and people work hard to hide it from others. Due to society’s misunderstanding of the disorder and the stigma attached to it, a person is left to deal with trichotillomania alone, often internalizing negative emotions.

- Hair pulling can interfere with school, work, relationships, and social activities.

- When unsuccessful at stopping the behavior, the negative emotional cycle of shame, embarrassment, and guilt can cause significant distress.

- Fear of judgment causes people to isolate socially.

Classification of Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania falls under a category of disorders called Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors (BFRBs), yet it is often misdiagnosed as other conditions. The most common misdiagnosis is OCD, followed closely by Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) and to some extent Non-suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI).

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

It is true that some people with OCD pull their hair and some people with trich have OCD. It is also true that trich is considered as part of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders. However, the primary difference is that a person with trich is driven by the behavior of pulling hair, not intrusive or obsessive thoughts. Whatever drives the urge, once hair is pulled, the urge is satisfied. On the contrary, a person with OCD may feel a compulsion to pull hair, but it is fueled by intrusive or obsessive thoughts which are not relieved once the hair is pulled. Also, trichotillomania is classified as a repetitive motor response whereas the behaviors of OCD are compulsive rituals that must be completed to satisfy an obsession. The age of onset is different as well. Trich tends to start in early adolescence while OCD starts in late adolescence. Each condition responds to treatment differently. Because of the behavioral focus of the disordered action, the evidence-based treatment for trich is Habit Reversal Training whereas OCD treatment is exposure and response prevention. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) help in treating OCD but show very little effectiveness for trich.

Trich

- Behavior-driven

- Repetitive motor symptom

- Starts in early adolescence

- Habit Reversal treatment

- SSRIs not effective

OCD

- Thought-driven

- Compulsive ritual

- Starts in late adolescence

- Exposure and response prevention treatment

- SSRIs effective

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

A person with body dysmorphic disorder becomes obsessed or preoccupied with a perceived defect in their physical appearance. In some cases, BDD can result in excessive hair pulling, but the goal of the behavior is to correct the perceived defect. For someone with trich, the goal is not to correct a defect.

Non-suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

When a person injures themselves without suicidal intent, it is called non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and often includes cutting, burning, or scratching. NSSI is thought to serve as a way to alleviate overwhelming negative emotion, as self-directed anger or punishment, or to influence others. While there are similarities between NSSI and focused trich, NSSI is a conscious decision to harm oneself as opposed to the compulsive urge to pull hair.

Effects of Trichotillomania

Physical Effects

Removing hair by the roots often damages the hair follicle. Once it is damaged, the hair may not grow back, or it may grow back in a way that does not match unpulled areas. Hair pulling causes skin damage when hair pulling occurs in the same area repeatedly ranging from mild skin abrasions to severe infections. Furthermore, if a person eats the pulled hair, they may develop hairballs in their digestive tract. These matted balls, known as trichobezoars, could grow over time as the hair accumulates causing vomiting, weight loss, intestinal obstruction, and death in some cases. If the ball gets large enough, intestinal or stomach surgery may be required to extricate it.

Psychological Effects

People who suffer from trichotillomania can feel an intense sense of shame, humiliation, and embarrassment over having the condition. These negative emotions can translate into depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. These feelings can expand even further outward into the realm of social isolation. Many people with trich avoid going outside or avoid intimacy out of fear that their disorder will be exposed. The psychological consequences of trichotillomania could also lead a person to unhealthy lifestyle choices such as drugs or alcohol to cope with negative emotions.

Treatment

Recovery is possible

Treatment involves learning to manage the urges and behaviors associated with trich. It is a lifelong, chronic condition which means that medical science has no cure. However, many people learn to manage and cope by integrating the physical, psychological, and social aspects of treatment. Recovery is a whole-person, whole-lifestyle effort not only dealing with behavior management, thought management and emotional regulation, but also dealing with the effects of shame, embarrassment, and stigma. Connecting with others who struggle with hair pulling provides a network of encouragement, education, information, and ideas.

Trichotillomania is often misdiagnosed or undiagnosed which causes more harm. When you look for a therapist, find an expert in body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs). BFRB experts know how to assess for behaviors and triggers, and they stay informed on the latest evidence-based treatment practices. They also understand that everyone experiences trich differently and can lead you through the process of increasing your awareness and identifying individualized treatment options.

It may be difficult to find a provider with experience treating trich. Internet-based therapy can be just as effective as in-person therapy. It does not matter if you have been in treatment before. According to a recent study, one’s history of previous treatment does not affect the outcome of Internet-based therapy. The important thing is to reach out for help and not to give up.

Physical

- Increase awareness of urges, triggers, and behaviors.

- Take care of your body internally by eating a healthy diet.

- Take care of your body externally by allowing damaged skin and hair follicles to heal properly.

- Manage urges, triggers, and behaviors.

- Manage stress.

- Ask your doctor if medications or supplements could help.

Psychological

- Engage in psychotherapy. Several therapeutic interventions show good results including cognitive behavioral therapy, habit reversal training, acceptance and commitment therapy, and comprehensive behavioral therapy. Some people report good results from hypnosis, group therapy, and alternative treatments.

- Deal with other mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, trauma, stress, and self-esteem.

- Practice good self-care.

Social

- Surround yourself with people who care for and support you.

- Enlist supportive others in your treatment.

- Participate in a support group in person or online.

- Learn how others learn to overcome the urges and manage behaviors.

- Help others.

For detailed treatment options, see our Trichotillomania Treatment page.