Body Dysmorphia, Hoarding, Hair Pulling, and Skin Picking: What Do They Have in Common?

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

Hair pulling, clinically known as Trichotillomania, is a disorder characterized by compulsive hair pulling that results in significant hair loss, emotional distress, and impaired psychosocial functioning. It is one of several disorders classified in DSM 5 as Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders. Other disorders included in this group of disorders include:

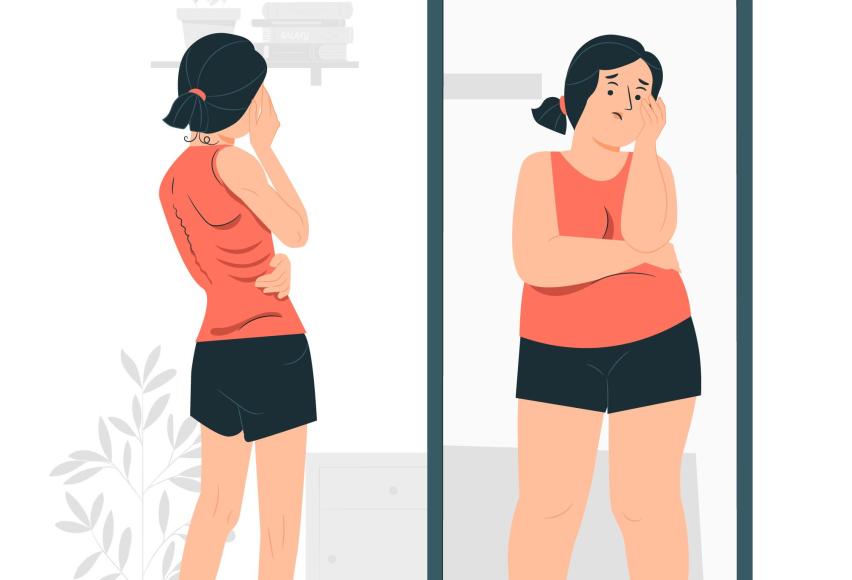

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) – BDD is a disorder characterized by excessive preoccupation with one or more perceived defects or flaws in one’s physical appearance that are not observable or appear slight to others. This preoccupation is typically accompanied by repetitive behaviors (e.g., mirror checking, excessive grooming, reassurance seeking) or mental acts (e.g., comparing one’s appearance with that of others).

- Hoarding Disorder (HD) – Hoarding disorder is characterized by a perceived need to keep and persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value. This difficulty results in the accumulation of items that clutter the living space and compromise its intended use.

- Excoriation/Skin Picking Disorder (SPD) – Excoriation/skin picking disorder is characterized by the repetitive picking of the skin resulting in skin lesions despite attempts to reduce or stop the behavior.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) – Perhaps the most well-known of the OCRDs, OCD is a disorder characterized by the presence of recurrent, persistent and intrusive thoughts, urges or images that cause marked anxiety or distress. The individual attempts to ignore or suppress such thoughts, urges, or images, or to neutralize them with some thought or action (i.e., by performing a compulsion).

While not the same as OCD, these disorders do share similar qualities with OCD and with each other:

- Obsessive or compulsive thoughts and ritualistic behaviors

- Difficulty controlling symptoms despite a desire to reduce or stop

- Avoidance of people or places due to due symptoms

- Emotional distress or impairment

- OCRDs generally emerge in late childhood or adolescence. Hair pulling, in fact, has what’s known as a bimodal onset meaning that there is an initial peak onset around age 7 to 8, and a second one in early adolescence.

The presence of OCRDs has been associated with a number of co-occurring mental health issues including depression, anxiety, decreased self-esteem, suicidal ideation, as well as reduced physical and psychological quality of life.

Despite the early onset of these disorders, most research has focused on adults. As a result, little is known about just how these disorders impact teens. In what is thought to be the first of its kind, a new study examined the impact of body-dysmorphic, hoarding, hair-pulling, and skin-picking symptoms in adolescence and how these symptoms relate to obsessive-compulsive, internalizing (e.g, depression, anxiety, fear) and externalizing (e.g., aggression, impulsivity) mental health symptoms, quality of life, suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm.

Impacts of OCRDs on Teens

Over 5000 teens participated in this study. Findings revealed clear associations between body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding, hair-pulling, and skin-picking symptoms and obsessive-compulsive, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, poor quality of life, suicide attempts, and non-suicidal self-harm.

- In this large sample, 3.7% of adolescents reported significant body-dysmorphic symptoms, 0.9% reported significant hoarding symptoms, 0.7% reported significant hair-pulling symptoms, and 1.8% of teens reported significant skin picking symptoms. The researchers suggest that these symptoms may be much more common than what would be expected at such young ages, since the rates are very similar to those reported in previous studies of adults.

- All symptom types were clearly associated with other mental health symptoms and poor quality of life.

- All symptom types were strongly associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm. Adolescents who scored above the clinical cut-offs of the symptom scales were much more likely to report that they had tried to commit suicide and engaged in non-suicidal self-harm during the last twelve months.

These disorders tend to be chronic and fluctuate in intensity over time. An early onset is associated with poor prognosis and greater comorbidity.

What Can Help?

Previous research with adults suggests that treatment tends to occur years after onset of symptoms. The rate of those who seek treatment tends to be low. Given the early onset of these disorders and the risks associated with self-harm and co-occurring mental health issues, early intervention may make a significant difference in reducing symptoms, providing support, and strengthening coping skills.

With most of the research done with adult samples, these findings speak to the need for the development of treatment approaches designed for adolescents. It’s also important for treatment providers to be well-trained in working with adolescents.

With the increased risk of suicide and self-harm associated with these disorders, it is imperative for healthcare providers from all disciplines to be mindful of and be able to accurately assess for risk. It’s not uncommon for a person’s first treatment encounter to be with a provider who is not a mental health professional. Especially with children and teens, their first encounter may be with their pediatrician or a dermatologist. Being able to identify the need for mental health support and working collaboratively with other disciplines can help provide the comprehensive treatment a teen may need. Psychodermatology is emerging as a way to help fill this need.

As we learn more about the unique experiences of teens living with an OCRD, it brings hope for more effective and targeted treatment approaches.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2. Moreno-Amador, B., Cervin, M., Falcó, R., Marzo, J. C., & Piqueras, J. A. (2022). Body-dysmorphic, hoarding, hair-pulling, and skin-picking symptoms in a large sample of adolescents. Current Psychology, 42(28), 24542-24553. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-022-03477-1#citeas

3. Marshall, C., Taylor, R., & Bewley, A. (2016). Psychodermatology in Clinical Practice: Main Principles. Acta dermato-venereologica, 96(217), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2370

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

Start your journey with TrichStop

Take control of your life and find freedom from hair pulling through professional therapy and evidence-based behavioral techniques.

Start Now